In my recent post I described the differences within the ceramic material found at Alvastra pile dwelling where the so called pile dwelling pottery (PBK) is singled out from the rest of the material partly through choices made during production. In my work it has therefore become important to evaluate how the different materials were produced.

The points that are of interest for me when characterizing the PBK are the use of temper, vessel-building technique, vessel thickness and shape as well as décor. This is why I now feel the need to explain Stone Age pottery production in detail, especially in regards to the material found within the pile dwelling.

The production of a vessel starts with a good choice of clay and temper. Previous analyses of the Alvastra pottery material has shown that the clay used when producing the pottery at the pile dwelling has partly been gathered in the nearby region (Hulthén 1998:53ff). Different types of temper have been used for different types of wares. Crushed granitic rock/granite, natural sand and crushed limestone have been used in the making of the vessels (see Hulthén 1998 for further details).

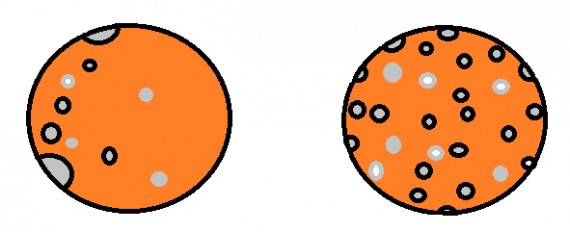

The progress of working the temper and clay together is the next step. Forming a “clay paste” where the temper and clay works together as desired, are of importance here. This act is similar to kneading dough when baking bread. The goal is to make a homogenized paste – and it takes time! I have found that a lot of sherds display wares that are poorly homogenized. Hulthén 1998, argues that it is foremost the so-called u-pottery that is poorly homogenized (Hulthén 1998:19). One thing is certain, the time spent on kneading the clay dough to form the PBK was short when compared to the funnel beaker pottery (FBP) and the PWC found at the site.

At the left a hypothetical section of poorly homogenized ceramic ware. At the right a hypothetical section of well homogenized ceramic ware.

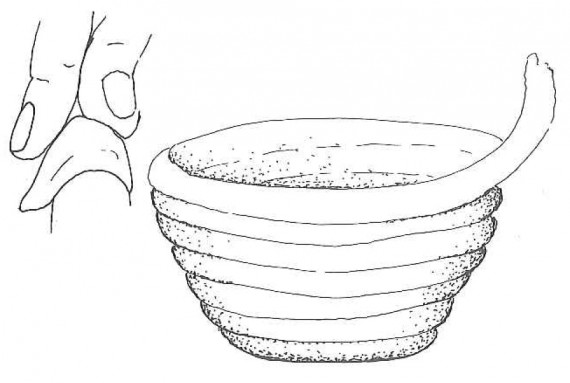

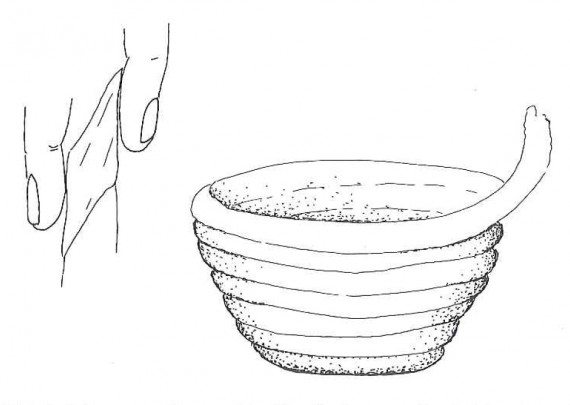

When the paste was done the Stone Age potters formed their vessels through coiling. The kneaded clay dough is now rolled into long clay rolls. The next step was to join these coils into a vessel. There are several ways through which the clay coils could be joined together and they are generally named h-/u- and n-technique (see Stilborg: 21 for further detail). The names of the techniques have to do with the finished product; how the coil joints look when joined together (see illustration below by Annika Jeppson in Keramik I Sydsverige 2002 pp. 22-23, published with permission from the artist).

Above, an illustration of the u-technique, where the clay coils are visible. Illustrations by Annika Jeppson in Keramik i Sydsverige 2002. Published with permission from the artist.

Above, an illustration of the n-technique where the clay coils are visible. Illustrations by Annika Jeppson in Keramik i Sydsverige 2002. Published with permission from the artist.

With the u-technique the coils are placed on top of each other and then joined in a downward dragging motion where the vessel wall is created. The section resembles a ‘U’ turned upside down (see illustration above). The vessels that are made with n-technique have coils that were placed on top of each other and flattened when joined through an upward dragging motion creating an N-shaped section (see illustration above). In order to make the vessel stabile and lasting this step has to be made carefully and not in a haste. However, the vessels can sometimes break along the coil joints revealing what technique was used. This is especially evident in the current material – could this also be a trace of a quickened pottery production at Alvastra?

Both the u- and n-techniques have been observed in the pile dwelling material. Hulthén reasons that the so called u-pottery differs from the n-pottery found at the site on several accounts including shape and ornamentation (Hulthén 1998:17).

The vessel shape is obtained when joining the coils together. The vessels found at the pile dwelling mostly have straight necks and rims. There are rounded and flat rims in the material as well. The rim diameters vary between 9 and 36 cm (Hulthén 1998:39). The shoulders are either rounded or profiled. The few base sherds that have been observed derived from flat or rounded bases (Hulthén 1998: 35).

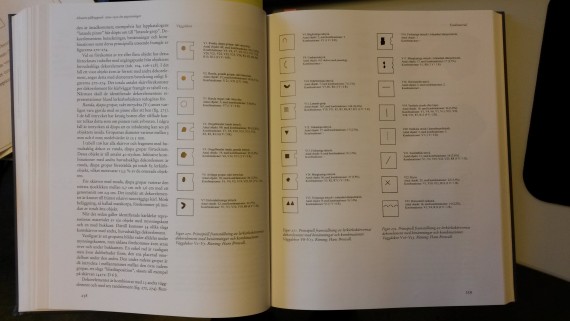

The choice of décor and surface treatment marks the end of the ceramic production prior to firing. The ceramic material at Alvastra displays an array of different décors. Some elements are ascribed to the FBP and some to the PWC. A few of them corresponds to the local PBK. When registering the material I have chosen to follow Hans Browalls scheme of decoration through which he has registered parts of the material (Browall 2011:258ff). This choice has been made in order to make the material more accessible for future research.

A picture of Hans Browalls scheme of decoration as it is published in his book Alvastra pålbyggnad. 1909-1930 års utgrävningar from 2011.

What seems to be specific for the PBK is the lack of incised décors. The decorated sherds observed so far have impressed décors. Hulthén show that the vessels that are made by means of u-technique are decorated below the rim and sometimes below the shoulder – very rarely on the rim (Hulthén 1998:23). The vessels that are made by means of the n-technique are, decorated below the rim, on the neck and below the transition from the shoulder to the body. Decoration on the rim edge occurs on flat edges (Hulthén 1998:39). It should be noted that a few sherds found outside the pile dwelling that are ascribed to the FBC have incised parallel and angular lines (Hulthén 1998:40).

Now, firing! The now decorated vessels are placed in an open fire at temperatures around 600°C (Hulthén 1998:35). Et voilà! A vessel is made.

References

Browall, H., 2011. Alvastra pålbyggnad. 1909-1930 års utgrävningar. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. Handlingar. Antikvariska serien 48. Stockholm

Hulthén, B., 1998. The Alvastra Pile Dwelling Pottery. An attempt to trace the society behind the sherds. The Museum of National Antiquites. Monographs 5. Stockholm.

Stilborg, O., 2002. Uppbyggnadsteknik. In: Lindahl, Olausson & Carlie (eds.) Keramik i Sydsverige. En handbok för arkologer. Malmö. pp. 21-24.

Illustrations

Where indicated illustrations by Annika Jeppson in: Lindahl, Olausson & Carlie (eds.) Keramik i Sydsverige. En handbok för arkologer. Malmö. pp. 22-23. Other illustrations made by the author.

Kommentarer (2)

Marvella Sapper

2015.11.09

I truly appreciate this blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

http://www.myowndomain12345d.com

Nathalie Dimc

2015.11.10

Hi Marvella,

I am glad that you appreciate the post. Thank you for telling us!